These days I find myself wishing to be the woman who writes this blog, not just when I sit in front of my computer but all the time. Her life is pretty good. She is a poet and a clinical researcher. She has an adorable toddler. She has a lovely house on a hill and the ability to watch sunrise caressing the winding trails and roads sprawled below her. She has the luxury to write about things lost and forgotten from a safe distance. There are a few people who like what she writes. Every day, she is able to get at least two uninterrupted hours of listening to audiobooks. She is poised to do bigger and better things. She is so positive in her writing. She talks about seizing the day and bottling up happiness and loving her naughty toddler. She talks about cooking and loving. Her life is pretty good from this vantage point. Pretty damn good. And I want to have her life all the time rather than during the single hour it takes me to write and proofread a blog post.

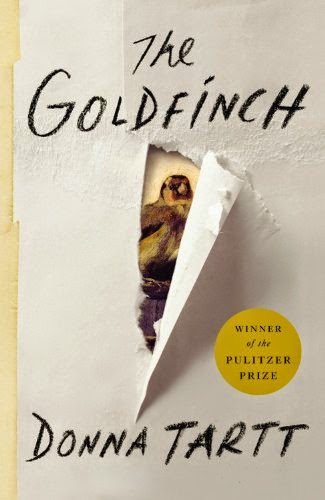

These days I find myself wishing to be the woman who writes this blog, not just when I sit in front of my computer but all the time. Her life is pretty good. She is a poet and a clinical researcher. She has an adorable toddler. She has a lovely house on a hill and the ability to watch sunrise caressing the winding trails and roads sprawled below her. She has the luxury to write about things lost and forgotten from a safe distance. There are a few people who like what she writes. Every day, she is able to get at least two uninterrupted hours of listening to audiobooks. She is poised to do bigger and better things. She is so positive in her writing. She talks about seizing the day and bottling up happiness and loving her naughty toddler. She talks about cooking and loving. Her life is pretty good from this vantage point. Pretty damn good. And I want to have her life all the time rather than during the single hour it takes me to write and proofread a blog post.  Yesterday, in a small group of smart and sensitive women that constitute the Desi Writers' Lounge Bay Area Readers' Club, we talked about The Goldfinch. I insisted that several characters in the book probably had personality disorders. Sahar Ghazi, an extremely perceptive member of the group and a dear friend, challenged me on this notion. "Why do you think they have personality disorders," Sahar asked. "We are learning about them only through the main character's perspective. Maybe they are completely normal and going through life on a pretense. Maybe they are not opening up their true selves in front of him. People live their life pretending sometimes," I am paraphrasing, but that is the general arc of Sahar's view. I think I presented a different and opposing argument, something feeble and completely petulant like, "But I don't pretend. And who pretends? How can they do that?" Puerile - to say the least.

Yesterday, in a small group of smart and sensitive women that constitute the Desi Writers' Lounge Bay Area Readers' Club, we talked about The Goldfinch. I insisted that several characters in the book probably had personality disorders. Sahar Ghazi, an extremely perceptive member of the group and a dear friend, challenged me on this notion. "Why do you think they have personality disorders," Sahar asked. "We are learning about them only through the main character's perspective. Maybe they are completely normal and going through life on a pretense. Maybe they are not opening up their true selves in front of him. People live their life pretending sometimes," I am paraphrasing, but that is the general arc of Sahar's view. I think I presented a different and opposing argument, something feeble and completely petulant like, "But I don't pretend. And who pretends? How can they do that?" Puerile - to say the least.  The fact is, everyone pretends to some degree. Yes, this is the space where I come to be honest with myself, call myself on things that I did wrong, and talk about how wronged I have felt in the past due to other people's insensitivity. But honesty has degrees, too. It has layers and components. Often people reveal part of a fact and it is up to the reader to brush off the sand occluding their vision from this partial truth, and like an archeologist, try to determine what the whole story is. Think about it. We do it all the time. The missing pieces are sometimes inherently present in what is revealed - the tone of voice, the choice of words, the tangent of the neck, the slope of shoulders, the audible sighs, the wistful eyes. The bright smile that is plastered on one's face as a confirmation of happiness has nothing on all these other overbearing signs, and some poor folks are just completely transparent - I am beginning to think I may be one of them.

The fact is, everyone pretends to some degree. Yes, this is the space where I come to be honest with myself, call myself on things that I did wrong, and talk about how wronged I have felt in the past due to other people's insensitivity. But honesty has degrees, too. It has layers and components. Often people reveal part of a fact and it is up to the reader to brush off the sand occluding their vision from this partial truth, and like an archeologist, try to determine what the whole story is. Think about it. We do it all the time. The missing pieces are sometimes inherently present in what is revealed - the tone of voice, the choice of words, the tangent of the neck, the slope of shoulders, the audible sighs, the wistful eyes. The bright smile that is plastered on one's face as a confirmation of happiness has nothing on all these other overbearing signs, and some poor folks are just completely transparent - I am beginning to think I may be one of them.  I guess what I am trying to get at in a very roundabout way is that we often think our best self is our happiest self. That is not necessarily true. I am a poet - my writing is dependent upon being miserable. The poems I write when I am happy do not resonate with me and probably not with my readers. I need superficial tragedies, arguments, disagreements, hurt feelings, a sense of being wronged in order to create work that has even a whisper of being placed at a lit mag. And though most of the time I bring my cheerful positive self to this blog (and I will not be surprised if you all stand up and say, "But Noor, you are a morose writer and you don't bring your cheerful self to this blog"), that is not my "normal" self. When I write in this space, I emulate the woman I want to be - the one who stands in her balcony every morning watching the sun bleed into the sky, the one who feels a sense of utter and profound contentment, the one who writes about life's little matters because, after all, those are the matters that matter. I wouldn't say that it is an entirely inaccurate depiction of myself, but it is certainly an extension of my character.

I guess what I am trying to get at in a very roundabout way is that we often think our best self is our happiest self. That is not necessarily true. I am a poet - my writing is dependent upon being miserable. The poems I write when I am happy do not resonate with me and probably not with my readers. I need superficial tragedies, arguments, disagreements, hurt feelings, a sense of being wronged in order to create work that has even a whisper of being placed at a lit mag. And though most of the time I bring my cheerful positive self to this blog (and I will not be surprised if you all stand up and say, "But Noor, you are a morose writer and you don't bring your cheerful self to this blog"), that is not my "normal" self. When I write in this space, I emulate the woman I want to be - the one who stands in her balcony every morning watching the sun bleed into the sky, the one who feels a sense of utter and profound contentment, the one who writes about life's little matters because, after all, those are the matters that matter. I wouldn't say that it is an entirely inaccurate depiction of myself, but it is certainly an extension of my character. You'll forgive me, of course, for this pretense, won't you? I am a poet who likes to experiment with identity and belonging. This is a natural result of that, you see. In any case, I wrote very honestly just now, and so I must extend my hand towards you in salutation. Hi! Good to meet you today!

Photos by Rebecca McCue