My grandmother did not leave trunks full of banarasi clothes, copper pots and pans, books, ledgers, deeds, wills, jewelry. She owned all of those things, but gave them away several years before she died. She sold the house she birthed 11 children in, the house from which two of her daughters' and her husband's funeral biers departed, the house that held memories of the 9 other children who lived and are now grandparents themselves. My grandmother kept limited belongings in her old age, a number that continued to dwindle as dementia took hold of her and made her a different person, not a lesser person, just different...and a little helpless. My grandmother's legacy, therefore, is not tangible. It is in the life-story she shared with her grandchildren on winter evenings with the gas heater blazing, peanut shells crackling between our fingers, candles lit up around us, the power having failed as usual. We would sit around her in a tight circle, tucked underneath heavy velvet quilts and listen to her story of crossing the border from Amritsar to Lahore with her husband and two little boys. Sometimes, she would sing us a song, a song I can't remember now, one that her own mother had sung to her. She told us about her father who died young, about her widowed mother's efforts to raise the family, about getting a scholarship to earn teaching credentials, financing her brother's foreign education, getting married, having kids, not quite understanding her husband. "I used to pray at night, you see," she'd say. "And your grandfather would call out to me over and over 'Zohra Begum! Come listen to me!' And I would just ignore him and wish for him to stop bothering me. I wonder all the time now, what it was he wanted to tell me."“This was another of our fears: that Life wouldn't turn out to be like Literature. Look at our parents--were they the stuff of Literature? At best, they might aspire to the condition of onlookers and bystanders, part of a social backdrop against which real, true, important things could happen. Like what? The things Literature was about: Love, sex, morality, friendship, happiness, suffering, betrayal, adultery, good and evil, heroes and villains, guilt and innocence, ambition, power, justice, revolution, war, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, the individual against society, success and failure, murder, suicide, death, God.”

― Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending

“How often do we tell our own life story? How often do we adjust, embellish, make sly cuts? And the longer life goes on, the fewer are those around to challenge our account, to remind us that our life is not our life, merely the story we have told about our life. Told to others, but—mainly—to ourselves.”

― Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending

|

| Stanford |

I am thinking about life-stories in the context of my own, of course. I identify as a poet, mother, and researcher, so in terms of my life-story, I will obviously focus on significant events associated with these aspects of my life. Those who know me best have often heard the dramatic telling of "How I Ended Up At Stanford" story, or "How I Edit Poetry" story, or "How I Have Raised Jahan" story. Since I no longer identify very strongly as a daughter by virtue of being an adult and having left the nest, I censor the formative years, which are rife with tragic and dramatic elements that would make for excellent narrative exposition. I do this very consciously. I have done it so often and so well that I have beguiled myself into thinking that those years simply don't matter in my life-story. Obviously, they do. The version of the story I tell myself, while being somewhat accurate, is most certainly not complete.

Thinking about all of this analytically, I

have reached some uneasy realizations. I am a dishonest story-teller. I

tell myself what I like to hear. This is all well and good until I

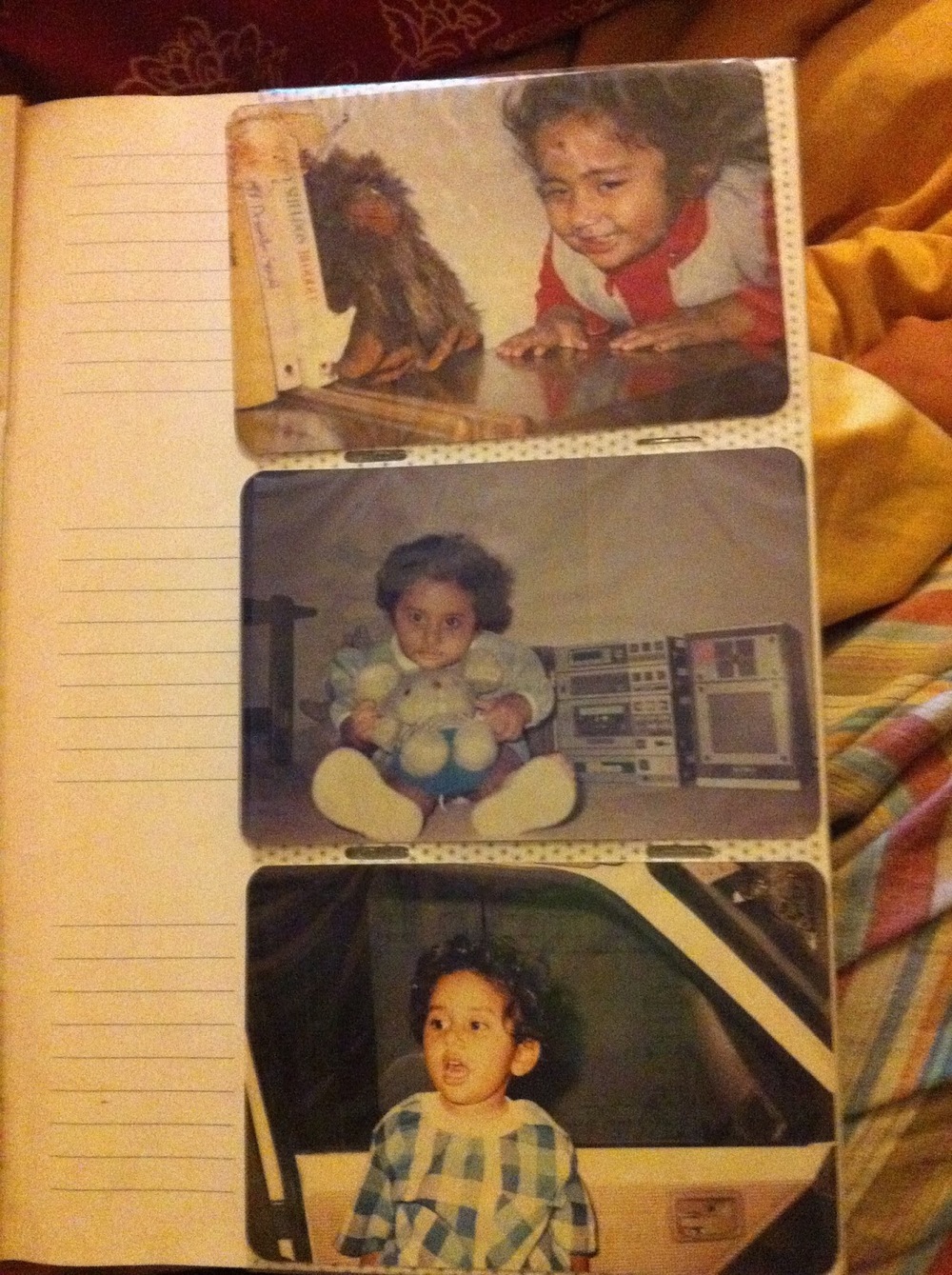

start to think about my legacy. I can't just erase the first 18 years of my life in Pakistan. And, quite frankly, I don't want to.

No one has a linearly ascending journey from point A to point B. Some

people stay at point A all their lives. Others, most commonly, climb and swoop and plateau and rise and fall, all the way from Point A to B. The trouble with my journey, and therefore, my story is that I have left point A far behind and am so bewildered by the pitfalls and advances in no-man's-land on the way to Point B, that everything is a little hazy - the past and the future.

Thinking about all of this analytically, I

have reached some uneasy realizations. I am a dishonest story-teller. I

tell myself what I like to hear. This is all well and good until I

start to think about my legacy. I can't just erase the first 18 years of my life in Pakistan. And, quite frankly, I don't want to.

No one has a linearly ascending journey from point A to point B. Some

people stay at point A all their lives. Others, most commonly, climb and swoop and plateau and rise and fall, all the way from Point A to B. The trouble with my journey, and therefore, my story is that I have left point A far behind and am so bewildered by the pitfalls and advances in no-man's-land on the way to Point B, that everything is a little hazy - the past and the future.  I need to start re-telling my story to myself, without self-pity and self-doubt. Before I can do that, though, I need to remember the story as accurately as possible. The more I think about the past, the more I am convinced that I need to re-examine it. I need to look at events from several different perspectives. Did he really mean it when he said XYZ, or was he trying to hurt me as I was trying to hurt him? You do hurt each other when you're angry, it's what you do to everyone you love, because you know they will forgive you. I need to reach out to the characters in my story, the characters that matter, and start a dialogue. Can we start from the beginning, please? Let's forgive each other, but let's not forget. I need you to remember. Remember with me. Let's write down our life-stories. This is how I remember it. Is this how you remember it, as well?

I need to start re-telling my story to myself, without self-pity and self-doubt. Before I can do that, though, I need to remember the story as accurately as possible. The more I think about the past, the more I am convinced that I need to re-examine it. I need to look at events from several different perspectives. Did he really mean it when he said XYZ, or was he trying to hurt me as I was trying to hurt him? You do hurt each other when you're angry, it's what you do to everyone you love, because you know they will forgive you. I need to reach out to the characters in my story, the characters that matter, and start a dialogue. Can we start from the beginning, please? Let's forgive each other, but let's not forget. I need you to remember. Remember with me. Let's write down our life-stories. This is how I remember it. Is this how you remember it, as well?Your life-story is not just about you. And it certainly didn't happen the way you've been telling it to yourself. Think about it - what did you leave out and why? It's not an easy conversation to have with yourself, but it's an important one.

(And, by the way, I highly recommend the book quoted in this blog entry, The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes.)

Photos 2 and 3 by Rebecca McCue