From the beginning, this is exactly how it was supposed to be.

Without ceremony or preamble, I am returning to Pakistan after nearly 14 years of being in California. I am traveling alone -- my daughter and husband, both of whom became a part of my life when I had already planted myself firmly in the identity of an immigrant, will stay behind. I am going for 10 days including travel time. Time, I imagine, will fly, but I will also have a heightened sense of its flight. I will feel it in its most concentrated form -- sort of like seeing heavily pigmented color, touching the purest of silk, experiencing the tug of life that pulls a baby into this world.

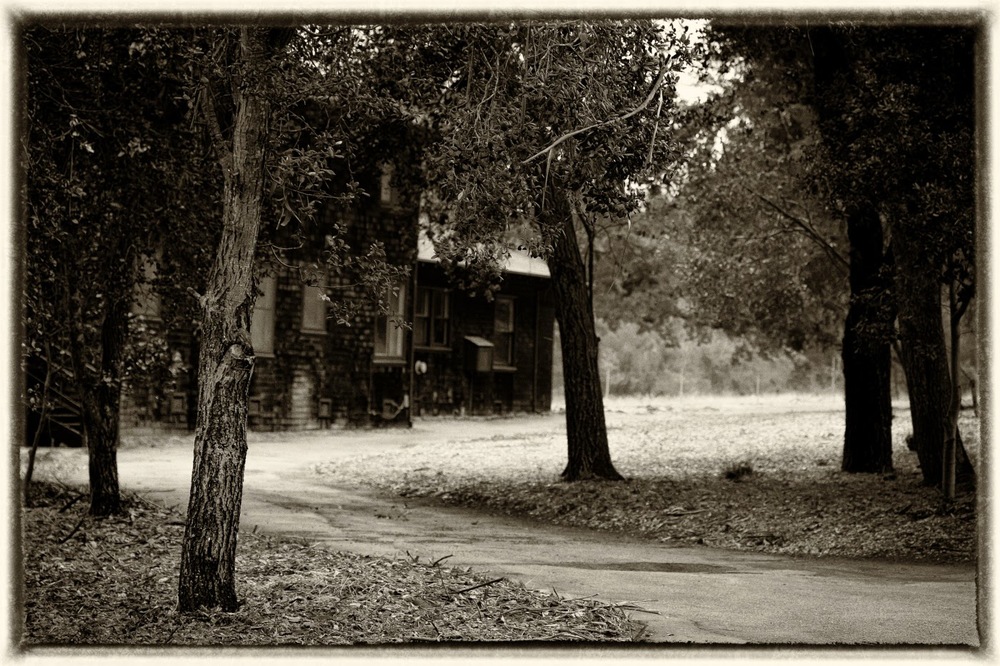

The anticipation frightens me. I am most afraid of finding out that the place that exists in my memory is inaccurate -- a composite of my imagination and past -- the Lahore I have been writing about is frozen only on the pages that I have filled. I feel each sense coming to attention in the days before my departure, ready to call me out as an imposter. I am perpetually at an impasse with myself. The places I remember are no longer a part of the city I was raised in. A few days ago, my sister asked me, "What do you remember?" And I said, "Kalma Chowk." Her smile held sympathy, "There is no Kalma Chowk anymore."

How does one reconcile with a loss that is not only intangible, but also indescribable? How does one begin to parse out the grief that surrounds estrangement? It didn't begin this way. In a lot of ways, this journey has been like seeing a child grow up. You know they are growing and changing, but you cannot trace the growth, hold them in your arms and realize that they have changed. But they are morphing into larger forms of themselves all the time, in front of your eyes, and you are blind to it until you see growth charts in a pediatrician's office, or see pictures of them from a few years ago or even a few months ago. It is only in retrospect, that you can see this magic -- the roundness of the face diminishing, the hair losing its curl, the child crawling, standing, walking, dancing... So fleeting, all of it, and yet it unfolds in precise detail for us without our notice. And so, when people ask me how is it that 14 years have gone by and I have not returned? How is it that I have managed to survive without the places and people I claim to love -- I only say, I don't know where the time went.

These days, I have started to dream again. My dreams are mostly about forgetting things, or losing people. There is a profound sense of urgency that envelops me when I emerge from sleep. It is disorienting to find myself in my bed, the house humming quietly in the night, everything just as I arranged it before sleep descended -- the robe over the chair, the cup of water on the coaster, the phone blinking in the dark bearing missives from a different time zone. But if I speak frankly, I might say the messages are from a different world altogether.

"How is mama?"

"What is the chemo schedule?"

"Don't bring presents."

"I love you."

"Mama is dealing with everything like a champ."

What is this world? How did we get here, dragged to this very point in our shared existence by distance, decisions, grief, sickness, choices, independence, detachment...? How is it that a journey home comes about suddenly, without ceremony or preamble, after nearly 14 years, when what looms before me is not the thousands of miles I must cross defenselessly traversing air currents, or the people I must face who have changed and grown and lived and died, or the city I must go to that is past its monsoon prime for the year and will surely punish me in many ways for being gone too long -- no, none of this matters. What really holds me in a death grip of confrontation is a neat row of packages I created and tied with bows and pushed into the farthest recesses of my consciousness. They are what lie in wait at each step between here and there. How does one unravel and remember what's taken years to forget? How does one even begin to try?

And despite all of this, I know with absolute conviction, it had to be this way. Like I said -- from the beginning, this is exactly how it was supposed to be.