I am

eating my lunch outside the office, where a bee is incessantly interrupting me

as I finish my salad. Maybe it is the Japanese Cherry Blossom perfume I am

wearing that's attracting this annoyance. It

has been an exceptionally humid two days (for the Bay Area). It reminds me achingly of Lahore. This weather is comforting and disconcerting at the same time. It is

comforting because my skin has memory of it. As the moist air touches me, my

body remembers feeling a sensation akin to this years ago in more humid

and much warmer climate. I almost expect large salty raindrops to fall on me and a

wind to give the rain direction and force. The humidity is disconcerting because it seems

out of place here in the bay area, and also because it only feels like a

half-memory, a half-shadow of what I left behind in Lahore. The day

doesn't have the same heavy, overbearing blanket of moisture that made my hair

curl and chest tight back in my home city. It doesn't have the same smells, flowers blooming, pakoras frying in recycled oil of questionable origins on street corners,

little boys and girls jumping in puddles on the street, smiling gleefully, cars

filling up with water on roads, and always the rain, the relentless monsoon

rain, which caused rivers to swell and crops to die and villages to flood. It

feels wrong here, this humidity, but also like a small, unassuming gift. Like

someone up there saying, "Here, have a piece of the past; a diluted, pencil-tracing-as-opposed-to-water-color-type

piece, but a gift nonetheless to feed your senses." It's much appreciated.

I am

eating my lunch outside the office, where a bee is incessantly interrupting me

as I finish my salad. Maybe it is the Japanese Cherry Blossom perfume I am

wearing that's attracting this annoyance. It

has been an exceptionally humid two days (for the Bay Area). It reminds me achingly of Lahore. This weather is comforting and disconcerting at the same time. It is

comforting because my skin has memory of it. As the moist air touches me, my

body remembers feeling a sensation akin to this years ago in more humid

and much warmer climate. I almost expect large salty raindrops to fall on me and a

wind to give the rain direction and force. The humidity is disconcerting because it seems

out of place here in the bay area, and also because it only feels like a

half-memory, a half-shadow of what I left behind in Lahore. The day

doesn't have the same heavy, overbearing blanket of moisture that made my hair

curl and chest tight back in my home city. It doesn't have the same smells, flowers blooming, pakoras frying in recycled oil of questionable origins on street corners,

little boys and girls jumping in puddles on the street, smiling gleefully, cars

filling up with water on roads, and always the rain, the relentless monsoon

rain, which caused rivers to swell and crops to die and villages to flood. It

feels wrong here, this humidity, but also like a small, unassuming gift. Like

someone up there saying, "Here, have a piece of the past; a diluted, pencil-tracing-as-opposed-to-water-color-type

piece, but a gift nonetheless to feed your senses." It's much appreciated.

Tokyo,

Japan - 4:38AM

My

middle sister, Qurat Noor, sleeps in her tiny studio apartment in the heart of

Tokyo. She only just went to sleep. The Fajr (dawn) prayer happens at

2:30AM in Tokyo these days. She either stays awake for the prayer or sets an

alarm to wake up at that time. We chat after she prays usually. We tell each

other things about our day, which are not really that important or exciting,

but we listen anyway because we are sisters. Often, I whine, and she

commiserates. A few hours from now, she will wake up and get ready for work.

Her husband will have left already. Qurat will lay out her clothes in her usual

habit, neatly ironed, and in order. A pair of pants, a long shirt, shoes and

socks, scarf and coat. Check, check, check, and check. She will make herself a

small breakfast. Maybe she will walk to her balcony and look at the cherry

blossom tree. Maybe she will think of me as she sips her chai or of our baby

sister as she puts on the scarf they bought together in London a few years ago,

without me. She will walk out and catch a train to her office where she gives

English language lessons to locals. Will she notice the weather? Will the air

that tingled my arms reach her in a few hours? Will she breathe it in and be

surprised because it smells like Japanese Cherry Blossom perfume, or will it

just mingle with the fresh fragrance of the gorgeous blooms all around her?

Will she instinctively reach into her handbag for her phone to find the screen

blinking, telling her that there is a new message from one of her sisters in

our WhatsApp group chat (titled, very unoriginally and rather aptly, Noor

Ladies Only)?

My

middle sister, Qurat Noor, sleeps in her tiny studio apartment in the heart of

Tokyo. She only just went to sleep. The Fajr (dawn) prayer happens at

2:30AM in Tokyo these days. She either stays awake for the prayer or sets an

alarm to wake up at that time. We chat after she prays usually. We tell each

other things about our day, which are not really that important or exciting,

but we listen anyway because we are sisters. Often, I whine, and she

commiserates. A few hours from now, she will wake up and get ready for work.

Her husband will have left already. Qurat will lay out her clothes in her usual

habit, neatly ironed, and in order. A pair of pants, a long shirt, shoes and

socks, scarf and coat. Check, check, check, and check. She will make herself a

small breakfast. Maybe she will walk to her balcony and look at the cherry

blossom tree. Maybe she will think of me as she sips her chai or of our baby

sister as she puts on the scarf they bought together in London a few years ago,

without me. She will walk out and catch a train to her office where she gives

English language lessons to locals. Will she notice the weather? Will the air

that tingled my arms reach her in a few hours? Will she breathe it in and be

surprised because it smells like Japanese Cherry Blossom perfume, or will it

just mingle with the fresh fragrance of the gorgeous blooms all around her?

Will she instinctively reach into her handbag for her phone to find the screen

blinking, telling her that there is a new message from one of her sisters in

our WhatsApp group chat (titled, very unoriginally and rather aptly, Noor

Ladies Only)?

London,

UK - 8:38PM

Mahey

Noor, "the fairest and youngest of them all," sits dejectedly in a

small room in London. Most of her packing is done. Her suitcase lies closed but

unzipped in a corner, the top flap resting like a parted lip, surly, angry.

Mahey's 3-week vacation was simply not enough for her to

absorb London through her skin until the next time she can visit this city that seems

to thrum through her body. If she could live in this city, she would probably

never miss Lahore. She has visited all the landmarks and tourist attractions.

She has gone shopping, had fish and chips while traveling, and watched a Bollywood blockbuster in the theater.

She was almost blown away at one of the beaches, the wind whipping her around,

taking hold of her hair and her coat, making her buckle down, brace herself. She has gotten to know the London underground better than

the roads of Lahore. She has also spent a lot of time just sitting in her room,

sometimes writing, sometimes not, mostly just feeling at peace with

the city sprawling around her, realizing that this is where her home should be.

She has loved London for years and planned this trip to revive herself,

collect her thoughts and energies, detox in a more granular way than of the

emotional or physical variety. She looks at her ticket and passport slipped

into a red Stanford folder I sent her. Does she register the fact that I, too,

touched the same piece of laminated cardboard that she has in her possession,

or does she only concentrate on the sad, heavy feeling of the looming goodbye,

much like the weather I am experiencing, but more like the one I am

remembering, the kind we loved and lived through, all three of us, together?

Mahey

Noor, "the fairest and youngest of them all," sits dejectedly in a

small room in London. Most of her packing is done. Her suitcase lies closed but

unzipped in a corner, the top flap resting like a parted lip, surly, angry.

Mahey's 3-week vacation was simply not enough for her to

absorb London through her skin until the next time she can visit this city that seems

to thrum through her body. If she could live in this city, she would probably

never miss Lahore. She has visited all the landmarks and tourist attractions.

She has gone shopping, had fish and chips while traveling, and watched a Bollywood blockbuster in the theater.

She was almost blown away at one of the beaches, the wind whipping her around,

taking hold of her hair and her coat, making her buckle down, brace herself. She has gotten to know the London underground better than

the roads of Lahore. She has also spent a lot of time just sitting in her room,

sometimes writing, sometimes not, mostly just feeling at peace with

the city sprawling around her, realizing that this is where her home should be.

She has loved London for years and planned this trip to revive herself,

collect her thoughts and energies, detox in a more granular way than of the

emotional or physical variety. She looks at her ticket and passport slipped

into a red Stanford folder I sent her. Does she register the fact that I, too,

touched the same piece of laminated cardboard that she has in her possession,

or does she only concentrate on the sad, heavy feeling of the looming goodbye,

much like the weather I am experiencing, but more like the one I am

remembering, the kind we loved and lived through, all three of us, together?

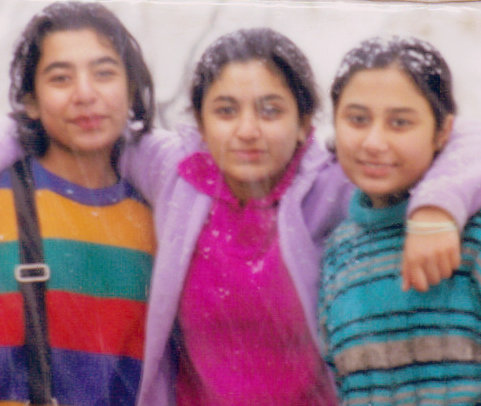

The

summer monsoons were important to us when we were little girls. They stood for buying new notebooks, large hardcover wide-ruled journals we

called "registers," A-4 papers, folders and binders, textbooks and

brown paper sheets to cover them. They made it possible to have long afternoons to read Enid

Blyton’s The Enchanted Woods series. They signaled the time for our mother to spend several evenings wrapping our books for the coming

school year and slapping a sticker on the front, on which I used to write the

owner’s name in my neat cursive hand. "Noorulain Noor, 3-C,"

"Quratulain Noor, 1-B," "Mahey Noor, Prep-A." They gave us

lots of time to play "teacher-teacher," in which we took turns for the role of "Miss Noor," writing on our small chalkboard, marking our

pretend assignments with swooping checks or crosses and adding comments in the

margins, "Good," "Excellent," "Poor,"

"Improvement needed." The monsoons also gave us a reason to sneak up to the roof in our sundresses

and run in the rain, our mother coming upstairs with towels, wrapping us in them, our hair wet and

flying every which way, our fingertips wrinkly, teeth chattering, lips blue.

They meant sleeping in every day, all three of us, tiny forms huddled on the

same bed, the middle sister appropriately sleeping in the middle - birth order

was ever so important back then.

The

summer monsoons meant so much more, too, though – mostly that we would be

together all day, every day, for the next three months. Twelve weeks that almost felt like a

lifetime to us. They seemed endless. Little did we know that by the time the

oldest one of us turned 18, we’d be separated, our childhoods nothing more than wavering shadows in

our lives.

|

| Murree, Pakistan. 1999. |